The Neuroscience of Addiction: Your Brain Hijacked?

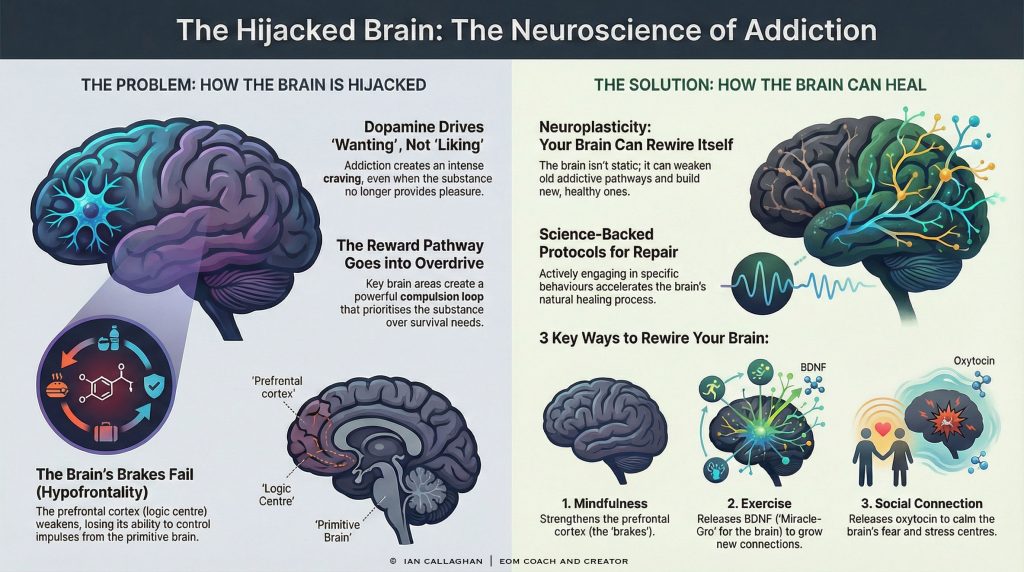

Stop blaming your character for a biological malfunction; deeply understanding The Neuroscience of Addiction: Explaining dopamine reward pathways to depersonalise the struggle is the absolute first step toward reclaiming your agency.

If you have ever found yourself staring at the ceiling at 3 AM, overwhelmed by shame after yet another relapse, you likely believe you are suffering from a defect of character. Society has spent decades reinforcing the idea that addiction is a choice—a simple failure of will. This narrative is not only damaging; it is scientifically incorrect. The reality is far less personal and far more mechanical. It is a matter of neurobiology, not morality.

By shifting our lens from the “moral model” to the “medical model,” we can begin to dismantle the immense shame that keeps people trapped in cycles of use. This guide bridges the gap between complex academic research and your lived experience. When you realise that evolutionary survival mechanisms have rewired your brain, the stigma begins to dissolve. You are not “bad.” You are battling a hijacked system.

The Evolutionary Trap: Why We Are Wired for Addiction

To understand addiction, we must first look at the human brain’s evolutionary architecture. We are not designed for the modern world of high-speed internet, synthetic opioids, or processed sugars. We are designed for the savannah.

The human brain has evolved in layers. Deep inside lies the limbic system, often called the “old brain” or “lizard brain.” This area is responsible for survival instincts: eating, drinking, mating, and avoiding danger. It is powerful, fast, and unconscious. Wrapped around it is the prefrontal cortex, the “new brain,” responsible for logic, decision-making, future planning, and impulse control.

Survival Over Logic

In a healthy brain, these two systems communicate effectively. The prefrontal cortex acts as a brake on the limbic system’s accelerator. However, the limbic system has seniority. When survival is on the line, the limbic system overrides logic.

Here lies the crux of the issue: Drugs and addictive behaviours hijack the survival system. They trick the brain into prioritising the substance or behaviour as highly as—or higher than—food and water. When an addiction takes hold, the brain does not interpret the craving as a desire for a “good time.” It interprets the craving as a life-or-death necessity.

This is why “just saying no” is rarely effective. You are not fighting a simple urge; you are fighting a survival drive that has been cross-wired. The neuroscience of addiction suggests that the brain treats the absence of the substance much like it treats starvation. The panic, the singular focus, and the willingness to take risks are all misdirected survival responses.

Decoding Dopamine: The Great Misconception

If we are to effectively discuss The Neuroscience of Addiction: Explaining dopamine reward pathways to depersonalise the struggle, we must correct the most common myth in popular psychology: the idea that dopamine is the “pleasure molecule.”

Dopamine is not about pleasure; it is about craving.

The Prediction Error

Neuroscientists define dopamine as a neurotransmitter involved in the prediction of reward errors. Its primary job is to tell your brain, “Pay attention! This is important for survival. Do it again.”

When you encounter something novel or rewarding, dopamine surges in the brain, creating a memory trace. It says, “That apple was sweet and gave us energy. Remember where the tree is. Go back tomorrow.”

In the context of addiction, substances or super-stimuli (like gambling or pornography) trigger an unnaturally high dopamine release—often up to ten times the amount produced by natural rewards like food or sex.

- Natural Rewards: Produce a moderate, manageable rise in dopamine that dissipates quickly.

- Addictive Agents: Produce a tidal wave of dopamine that floods the system and stays longer than nature intended.

Wanting vs. Liking

This distinction explains a phenomenon that baffles friends and family of those struggling with addiction: Why do they keep doing it if they don’t even enjoy it anymore?

Over time, the brain adapts to the chemical flood. The sensation of pleasure (hedonic impact) decreases due to tolerance. However, the dopamine system (incentive salience) remains hyperactive. This leads to a terrifying state where the individual has a desperate, screaming need (wanting) for the substance, even if they experience zero pleasure (liking) from it. You are chasing the relief of the craving, not the high itself.

The Mesolimbic Pathway: Anatomy of a Hijacking

To truly depersonalise the struggle, we need to examine the specific machinery of the brain. The “Reward Pathway,” scientifically known as the Mesolimbic Dopamine Pathway, is the central highway for addiction.

This pathway connects several key regions of the brain. When you engage in an addictive behaviour, electricity and chemicals shoot down this highway, reinforcing the neural connection.

1. The Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA)

The journey begins here. Located at the top of the brainstem, the VTA is the factory for dopamine production. When you encounter a trigger—a visual cue, a specific location, or even a mood—the VTA is activated. It sends a massive projection of dopamine to other areas of the brain.

2. The Nucleus Accumbens (NAc)

This is the brain’s “motivation centre.” When the dopamine from the VTA hits the Nucleus Accumbens, it acts as a green light. It compels action. It transforms the chemical signal into motor output: walking to the shop, dialling the dealer, or opening the app.

In an addicted brain, the NAc becomes hypersensitive to cues. If you are trying to quit drinking, simply walking past a pub can trigger the VTA to flood the NAc with dopamine. Before you have even consciously thought about a drink, your motor cortex is being prepped for action. This happens milliseconds before your conscious mind realises it.

3. The Amygdala

The Amygdala handles emotional processing and stress. In the context of addiction, it creates a conditioned response. It establishes the “anxiety” or “unease” you feel when the substance is missing. It remembers the relief the substance brought in the past and screams at the VTA to fix the current stress.

4. The Hippocampus

This is the memory centre. It records the context: Where were we? Who were we with? What music was playing? This is why specific environments can trigger massive cravings years after recovery. The Hippocampus provides the map; the VTA provides the fuel; the Nucleus Accumbens drives the car.

Hypofrontality: When the Brakes Fail

Perhaps the most critical concept in The Neuroscience of Addiction: Explaining dopamine reward pathways to depersonalise the struggle is the phenomenon of Hypofrontality.

While the “Old Brain” (VTA and NAc) is screaming for the substance, the “New Brain” (Prefrontal Cortex) is supposed to step in and say, “No, we have work tomorrow,” or “No, this will ruin our health.”

The Eroding Cortex

Chronic exposure to addictive substances physically alters the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC). Imaging studies show that in individuals with severe substance use disorders, the grey matter in the PFC is reduced. The neural connections between the PFC and the reward centre are weakened.

This state is called Hypofrontality. It literally means “low frontal activity.”

Imagine a high-performance sports car (your reward system) speeding down a hill. The Prefrontal Cortex is the braking system. In a non-addicted brain, the brakes are well-maintained. In an addicted brain, the brake lines have been cut.

The Loss of “Top-Down” Control

This explains the loss of control that characterises addiction. It is not that the person wants to ruin their life; it is that the biological mechanism required to stop the impulse is offline.

- Top-Down Control: The conscious mind regulates impulses (Logic > Emotion).

- Bottom-Up Drive: Impulses hijacking the conscious mind (Emotion > Logic).

During active addiction, the brain shifts to “Bottom-Up” dominance. The impulses from the primitive brain bypass the logic centre entirely. By the time the Prefrontal Cortex comes back online (often after the substance has been consumed), the damage is done. This leads to the immense guilt and confusion: “I promised myself I wouldn’t, so why did I?” The answer is that the part of the brain responsible for keeping that promise was chemically silenced at the critical moment.

Tolerance and Homeostasis: The New Normal

To understand why the struggle persists even after the initial “high” is gone, we must discuss homeostasis. The brain is a biological thermostat. It seeks balance above all else.

When you consistently flood the brain with dopamine (be it through opioids, cocaine, alcohol, or high-stakes gambling), the brain attempts to protect itself from over-stimulation. It realises that the volume is too loud, so it tries to turn it down.

Downregulation of Receptors

The brain achieves this balance through a process called downregulation. It reduces the number of dopamine receptors (specifically D2 receptors) available in the reward pathway.

Think of dopamine as a key and the receptors as locks. If you have too many keys floating around, the brain changes the locks and boards up the doors.

The Anhedonic Flatline

This adaptation leads to a state called Anhedonia—the inability to feel pleasure. Because the natural baseline for dopamine reception has been lowered to account for the drugs, “normal” rewards no longer register.

- A hug from a partner? Not enough dopamine to open the remaining locks.

- A nice meal? Barely registers.

- A promotion at work? Emotional flatline.

The only thing that produces enough dopamine to breach the threshold and make the person feel “normal” (not even high, just functional) is the addictive substance. This is the physiological trap. The user is no longer seeking euphoria; they are self-medicating a dopamine-deficient brain to feel a baseline level of okay.

This biological reality is vital for family members to understand. The behaviour is not a rejection of their love; it is a physiological inability to process the reward of that love due to receptor downregulation.

The Role of Glutamate: Cementing the Habit

While dopamine gets all the headlines, another neurotransmitter plays a darker role in the permanence of addiction: Glutamate.

Glutamate is the brain’s primary excitatory neurotransmitter. It is responsible for memory formation and the solidification of habits. While dopamine initiates the learning (“Do this again”), glutamate cements it (“This is now a permanent pathway”).

The Super-Highway

In the addicted brain, glutamate thickens the neural pathways associated with drug-seeking. It turns a dirt track into a six-lane motorway. This is why addiction is often referred to as a disease of memory and learning. The brain has “over-learned” the addiction.

When a person enters recovery, dopamine levels may eventually normalise, but these glutamate-reinforced pathways remain etched deep in the brain. This is the neurobiological basis for relapse. Even years later, stress can trigger a release of glutamate that reactivates these dormant motorways, causing an intense, physical compulsion to use.

Understanding glutamate helps us realise that recovery is not just about “detoxing” chemicals from the blood; it is about the long, slow process of pruning these super-highways and building new roads (neural pathways) through Neuroplasticity.

(End of Part 1. In Part 2, we will explore Neuroplasticity, the specific effects of stress on the addicted brain, and evidence-based protocols for reversing the damage.)

Can You Rewire Your Brain After Addiction?

The Neuroscience of Addiction: Explaining dopamine reward pathways to depersonalise the struggle reveals that while the brain can be hijacked by chemistry, it also possesses an extraordinary capacity to heal itself through Neuroplasticity.

If Part 1 of this guide illustrated how the brain gets “stuck” via dopamine and glutamate, Part 2 focuses on the mechanism of liberation. We move from the problem of fixed neural pathways to the solution of synaptic pruning and structural repair. Understanding this biology is the ultimate tool for self-compassion; it proves that the struggle is not a flaw of character, but a physiological challenge that requires biological interventions.

Neuroplasticity: The Double-Edged Sword

For decades, scientists believed that the adult brain was static—that once we reached adulthood, our neural wiring was fixed. We now realise this is false. The brain is neuroplastic; it is malleable and constantly reorganising itself based on input.

In the context of substance use disorder, Neuroplasticity is a double-edged sword. It is the very mechanism that allowed the addiction to form in the first place (by reinforcing the dopamine reward pathways). Still, it is also the mechanism that allows for recovery.

Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) vs. Long-Term Depression (LTD)

To understand how we rewire the brain, we must realise two biological processes:

- Long-Term Potentiation (LTP): This is the strengthening of synapses. When you use a substance, neurons fire together intensely. The brain says, “This is important,” and builds a thicker connection. This is how the “super-highway” of addiction is built.

- Long-Term Depression (LTD): This is not emotional depression, but a reduction in the efficacy of neuronal synapses. It is the process of weakening connections that are no longer used.

Recovery is essentially the active practice of inducing LTD on drug-seeking pathways while using LTP to build new pathways for healthy coping mechanisms. When you feel a craving but choose a recovery behaviour (like calling a sponsor or going for a run), you are physically starving the old neural highway and laying tarmac on a new road.

Hypofrontality: Why Willpower Often Fails

One of the most painful aspects of addiction is the disconnect between a person’s values and their behaviour. A loving parent may spend the family’s rent money on gambling; a dedicated professional may lose their job due to drinking. This is often judged as moral bankruptcy, but neuroscience offers a different explanation: Hypofrontality.

The brain functions as a hierarchy.

- The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC): This is the “CEO” of the brain. It handles logic, decision-making, impulse control, and future planning.

- The Midbrain (Limbic System): This is the “survival” centre. It handles drives like hunger, thirst, and the dopamine responses discussed in Part 1.

The Hijacking of the CEO

In a healthy brain, the PFC (the CEO) exerts “top-down” control over the midbrain. It can say, “I am hungry, but I will wait for dinner.”

In an addicted brain, chronic exposure to dopamine surges damages the connection between the PFC and the midbrain. Blood flow and glucose metabolism in the PFC significantly decrease. The car’s brakes are cut.

When a cue triggers a dopamine release, the midbrain screams “Survival!” (interpreting the drug as necessary for life). Because of Hypofrontality, the PFC is too weak to override this signal. The person is effectively functioning with their logic centre offline. This helps depersonalise the struggle: you are not making “bad choices” in a vacuum; you are operating with a compromised decision-making apparatus.

The Anti-Reward System: Why Stress Causes Relapse

If dopamine drives the “binge/intoxication” stage of addiction, the “withdrawal/negative affect” stage is driven by the HPA Axis (Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis).

When the brain is flooded with artificial dopamine, it attempts to maintain homeostasis (balance) by recruiting stress neurotransmitters, specifically Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF) and Dynorphin. These chemicals make us feel anxious, irritable, and dysphoric.

The Dark Side of Addiction

Dr George Koob, a leading researcher in this field, calls this the “Anti-Reward System.” Eventually, a person continues to use substances not to feel high (the reward system has burnt out), but simply to stop feeling the crushing anxiety of the anti-reward system.

This creates a state of AAnhedonia, the inability to feel pleasure from natural rewards like food, socialising, or sex.

This explains why stress is the number one predictor of relapse. When a recovering addict faces a stressful situation (an argument, a bill, a bad day), their HPA axis is already hypersensitive. It releases a flood of stress hormones that the compromised brain cannot handle. The brain immediately screams for the only thing it knows will quell the stress: the substance.

Understanding the HPA axis helps us realise that early recovery requires aggressive stress management, not just willpower.

Evidence-Based Protocols for Rewiring

We can use The Neuroscience of Addiction: Explaining dopamine reward pathways to depersonalise the struggle to create a roadmap for repair. Recovery is not magic; it is the biological process of repairing the PFC, calming the HPA axis, and normalising dopamine sensitivity.

Here are the most effective, science-backed protocols for accelerating this Neuroplasticity.

1. Mindfulness and Meditation: Strengthening the PFC

Mindfulness is often dismissed as spiritual fluff, but MRI scans prove it is a gym for the brain. Consistent mindfulness practice increases grey matter density in the Prefrontal Cortex.

By practising the act of noticing a craving without acting on it (often called “urgesurfing”), you are strengthening the top-down control of the PFC. You are literally repairing the brakes. This helps the individual pause between the trigger and the response, giving the logical brain time to come back online.

2. High-Intensity Exercise: The BDNF Boost

Exercise is perhaps the most potent biological tool for recovery. Cardio exercise triggers the release of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF).

Think of BDNF as “Miracle-Gro” for the brain. It supports the survival of existing neurons and encourages the growth of new synapses. High levels of BDNF accelerate Neuroplasticity, helping the brain learn new, healthy habits faster. Furthermore, exercise naturally increases dopamine and endorphins, helping alleviate AAnhedonia in recovery.

3. Social Connection: Regulating the Limbic System

The opposite of addiction is not sobriety; the opposite of addiction is connection. This famous adage has a neurochemical basis.

Social isolation increases stress hormones and sensitises the dopamine pathways to drugs. Conversely, positive social interaction releases Oxytocin. Oxytocin binds to receptors in the reward centre and calms the Amygdala (the brain’s fear centre).

Attending support groups (like AA, SMART Recovery, or therapy groups) does more than provide advice; the very act of shared vulnerability regulates the nervous system and lowers the threshold for craving.

4. Nutritional Psychiatry: The Gut-Brain Axis

95% of the body’s serotonin and 50% of its dopamine are produced in the gut. A diet high in processed sugar and inflammatory fats can exacerbate the inflammation already present in an addicted brain.

To support the synthesis of neurotransmitters, the recovering brain needs:

- Amino Acids: The building blocks of dopamine (Tyrosine) and serotonin (Tryptophan).

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Critical for cell membrane health in the brain.

- Complex Carbohydrates: To provide a steady supply of glucose to the energy-starved PFC.

Conclusion: Biology is Not Destiny

The journey through The Neuroscience of Addiction: Explaining dopamine reward pathways to depersonalise the struggle leads us to a singular, empowering conclusion: Addiction is a mechanical failure of the brain’s reward and impulse control systems, not a failure of the soul.

We have seen how dopamine hijacks the “wanting” system, how glutamate cements the memory of the drug, and how the prefrontal cortex loses its ability to say “no.” We have looked at how the anti-reward system traps a person in a cycle of stress-induced use.

But we have also seen that the brain is resilient. Through the mechanisms of Neuroplasticity, the “super-highways” of addiction can be overgrown with disuse, and new paths of recovery can be paved.

By shifting the narrative from “I am weak” to “My brain needs repair,” we remove the shame that keeps so many people sick. When we view addiction through the lens of neuroscience, we treat it with the same clinical precision and compassion as we would a broken bone or a cardiac condition.

The struggle is real, but the wiring is reversible. With time, patience, and the right inputs, the brain can, and will, heal itself.

Emotional Mastery: The Emotional Operating System

The Emotional Mastery book is a practical manual for understanding and regulating the human nervous system using the Emotional Operating System framework.

Instead of analysing emotions or retelling your past, the Emotional Mastery book teaches you how to read emotional states as system feedback, identify overload, and restore stability under pressure.

No labels. No therapy-speak. No endless healing loops.

Just a clear, operational approach to emotional regulation that actually holds when life applies load.

Instant digital download.