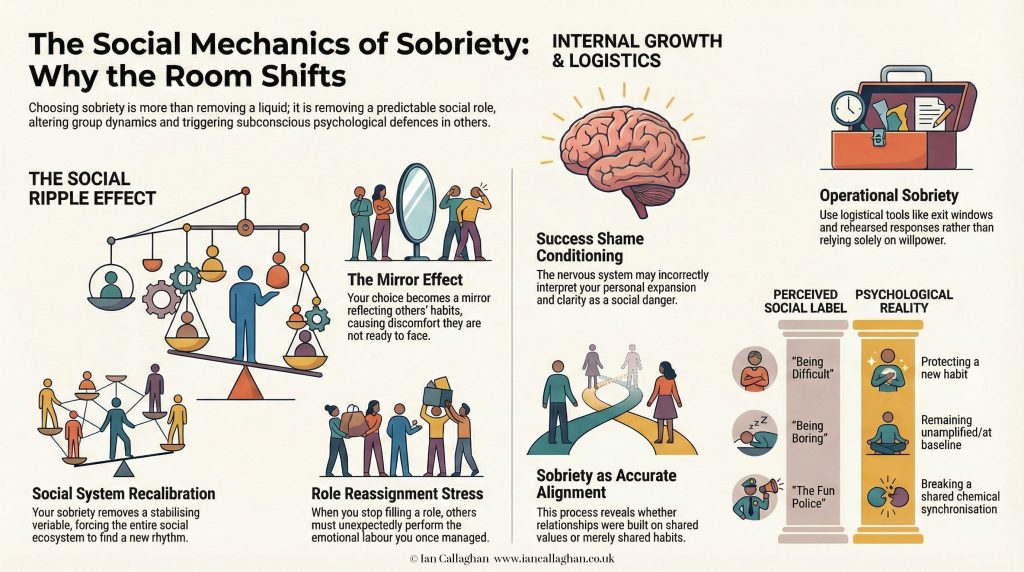

Why Your Sobriety Makes Other People Uncomfortable: The Hidden Mathematics of Social Dynamics

Introduction: The Family BBQ and the Invisible Contract

Picture a typical British family BBQ. The afternoon sun is beginning to dip, casting long, amber shadows across the lawn. The air is heavy with the scent of charcoal, sizzling fat, and the rhythmic, percussive clink of glass against glass. There is a specific cadence to this environment—a shared, unwritten choreography of pouring, topping up, and clinking that has been rehearsed by your kin for decades. Now, imagine yourself standing in the centre of this familiar scene, holding a glass of sparkling water with a solitary wedge of lime.

The condensation on your glass is cold, but the social atmosphere has suddenly become uncomfortably warm. You become acutely aware of the “social air pressure” shifting. It is a molecular change in the room’s ease. You notice the lingering glances at your glass, the subtle pauses in conversation, and the unspoken questions that seem to hang in the air like the smoke from the grill. This moment is not actually about the absence of ethanol in your system; it is a moment of profound revelation regarding a set of “invisible social contracts.”

These are the agreements you never signed but were handed at birth, renewed every weekend, and reinforced through every shared toast. These contracts dictate not just how you should behave, but how your behaviour should serve the emotional comfort of the collective. When you choose sobriety, you are doing something far more disruptive than changing your beverage. You are opting out of a neurological and social agreement that governs the group’s rhythm.

We often mistakenly frame the decision to stop drinking as a purely chemical one—a matter of biology, liver enzymes, and willpower. However, the reality is that sobriety is a profound social and neurological shift wrapped in a chemical habit. It is reinforced by repetition, ritual, and the environments we inhabit. This article will move beyond the visible layer of the liquid in your glass to explore the “hidden mathematics” of group dynamics. We will examine why your personal evolution feels like a systemic threat to others and how to navigate the structural recalibration that occurs when one person decides to stop playing their assigned role in the social ecosystem.

2. You Aren’t Just Removing a Liquid; You’re Removing a Role

The most common misconception about the sober journey is that it is a subtractive process. We focus on what is being “taken away”—the wine, the beer, the late-night shots. In reality, alcohol is merely the visible layer of a much more complex social architecture. When you stop drinking, you aren’t just removing a liquid; you are removing a role that the group has come to rely upon for its own “efficiency.”

Every social group, from family units to corporate teams, functions as a small-scale ecosystem. To conserve cognitive energy, groups assign their members specific functions. These roles are rarely discussed, but they are essential for the group’s stability. For years, you likely occupied a specific slot in the group’s “Hidden Mathematics”:

- The Funny One: The person tasked with keeping the mood light and the jokes flowing, ensuring that the group never has to touch upon serious or uncomfortable topics.

- The Loud One: The individual who provides the “volume” and energy, acting as a human shield against awkward silences.

- The One Who Stayed Late: The reliable anchor whose presence ensures the party never has to end, validating the group’s collective excess.

- The Emotional Buffer: The one who diffuses tension by suggesting “another round” whenever a conversation becomes too intimate or volatile.

- The Comparative Excess: The most vital role of all. This is the person whose heavy drinking allows everyone else to point and say, “At least I’m not as bad as them,” thereby protecting their own denial.

The group finds these roles “comfortable” because they reduce the social energy required to navigate uncertainty. When everyone stays in their assigned slot, the outcome of any social gathering is guaranteed. However, when you quietly announce, “I’m not drinking,” you are effectively resigning from your post.

“What you are witnessing is not drama. It is system recalibration. You have removed a stabilising variable from a small social ecosystem.”

By declining a drink, you have altered the mathematics of the group dynamic. You have changed the expected outcome of a shared situation. Because the human brain is a pattern-recognition machine, any change in a long-standing pattern feels like a transgression. The “social air pressure” changes because the group now has to do the hard work of finding a new equilibrium without your previous contribution.

Reflection/Analysis: The Perception of Betrayal Why does changing the expected outcome of a social situation feel like a betrayal? To understand this, we must look at the concept of social energy conservation. Groups rely on shared predictability for emotional safety. When you occupy a specific role—especially that of the “drinker” or “peacemaker”—you are providing a service that allows others to remain in their comfort zones. By stepping out of that role, you force the group to perform “emotional labour.” They now have to face the silences you once filled or the tensions you once diluted. To the group’s subconscious, your sobriety isn’t a personal health choice; it is an act of industrial sabotage against the group’s emotional ease. The feeling of betrayal they experience is actually the friction of being forced to think and feel in ways they have spent years avoiding.

3. The Mirror Effect: Why the Room Gets “Weird”

When a room “gets weird” after you reveal your sobriety, it is rarely due to a moral judgement of your character. Instead, it is the result of three specific psychological mechanisms: Projection, The Mirror Effect, and Cognitive Dissonance. Understanding these allows you to see the reaction of others as an automatic neurological response rather than a personal attack.

Projection Often, when you feel judged for not drinking, you are actually witnessing an externalised version of the other person’s internal audit. Their brain is performing a rapid, uncomfortable comparison between your clarity and their own intoxication. To reduce the tension of this comparison, they project their discomfort onto you. Instead of the brain asking, “Why am I feeling defensive right now?” it takes a cognitive shortcut: “Why is this person being so difficult?” By labelling you as “boring” or “preachy,” they protect themselves from having to perform a painful audit of their own habits.

The Mirror Effect Your glass of lime and soda acts as a mirror that the people around you did not ask to look into. Alcohol provides a “soft focus” for life’s rougher edges, blurring the reality of one’s health, anxiety, and choices. When you show up sober, you sharpen that focus for everyone in the room. Your presence raises silent, haunting questions: If they have the capacity to stop, why don’t I? If they look this much healthier, what am I doing to my own body? Humans are hardwired to avoid mirrors that reflect behaviours they aren’t ready to change. Your sobriety removes the blur, forcing others to see their own relationship with alcohol with unwanted clarity.

Cognitive Dissonance Most people who drink hold two conflicting beliefs: “I deserve this drink for stress relief” and “I know this habit is undermining my potential.” This creates a state of cognitive dissonance—a psychological tension the brain loathes. Your visible improvement and newfound boundaries increase this tension for those around you. The brain seeks the path of least resistance to resolve this. One option is self-reflection and change (difficult). The other is “social correction” (easy). If they can nudge you back into drinking, your return to your old role restores their comfort and makes their own dissonance vanish.

“It is easier to label you boring than to question their own reliance on alcohol for confidence or relief.”

Reflection/Analysis: The Sharpened Focus The idea that sobriety “sharpens the focus” of a room is central to the discomfort you witness. Alcohol acts as a behavioural synchroniser; it creates a shared chemical baseline that allows everyone to operate at the same “frequency.” When you opt out, you remain at your baseline while others are “amplified.” This lack of synchronisation makes you appear like a static element in a moving picture. You aren’t doing anything to judge them, but your mere presence at a different “clarity level” acts as a silent witness to the group’s escalating excess. The room gets “weird” because you have removed the “chemical blur” that usually facilitates social ease, making the “unblurred” reality of the situation visible to everyone, whether they want to see it or not.

4. The Status Shift: Navigating Normalisation Pressure

Social groups operate on subtle, unspoken hierarchies of behaviour, humour, and tolerance. There is often an informal “pecking order” where being “one of us” is the highest status one can achieve. This status is maintained through “normalisation”—the act of everyone adhering to the same shared behaviours to ensure group cohesion.

When you stop drinking, your alcohol tolerance drops to zero, and in the eyes of the group, your status undergoes a radical shift. You have moved from “one of us” to “different.” In evolutionary terms, “different” is often interpreted as a threat to the tribe’s safety. This triggers “normalisation pressure,” a series of subtle (and sometimes aggressive) nudges intended to return the group to its previous equilibrium.

You will likely encounter the “Nudge Script”:

- “Go on, just have one for the toast.”

- “You’ve changed; you used to be the life of the party.”

- “Don’t be boring; it’s a celebration.”

- “You need to learn how to live a little.”

These phrases are rarely acts of intentional cruelty. They are examples of “subconscious pattern preservation.” The people saying them are essentially pleading with you to go back to the version of yourself that required less emotional effort from them. Your “difference” triggers uncertainty, and uncertainty is interpreted by the primitive brain as danger. By using jokes or peer pressure, the group is attempting to bring you back to the “shared baseline” where everything felt “safe.”

Reflection/Analysis: The Safety of the Normal To a social group, “normal” feels safe because it is predictable. When a group has a shared habit, that habit becomes a pillar of their collective identity. When you step away from that pillar, you aren’t just making a personal choice; you are challenging the group’s very definition of “normal.” This creates a sense of instability that triggers the amygdala. The group’s reaction—the rolling of eyes or the “boring” label—is a defensive mechanism. They are trying to protect the group’s “safe zone” from the uncertainty your change has introduced. It is always easier for a group to pressure an individual to conform than it is for the group to reconsider its own definition of safety.

5. Family Systems: The Closed Loop Resistance

While friend groups can be challenging, family systems present a unique set of difficulties because they are “closed loops.” A family is not just a collection of individuals; it is a behavioural ecosystem with deep memory, tradition, and immense emotional inertia.

Families run on invisible agreements about roles that have been reinforced over decades. Perhaps you were the peacemaker who used a bottle of wine to diffuse holiday tension, or the “entertainer” whose drunken antics were the highlight of every gathering. In many families, alcohol is the “glue” that keeps difficult, buried conversations from rising to the surface.

Role Reassignment Stress When you step out of your established role, you create a “gap” in the family system. This leads to “Role Reassignment Stress.” If you were the one who always filled the silence, someone else now has to sit with that void. If you were the one who diluted the tension, someone else now has to face it head-on. Humans naturally resist this reassignment because it forces them to take on “emotional labour” they never volunteered for. The family system will often attempt to “correct” you back into your old role simply to avoid the stress of having to adjust.

The Support to Sabotage Spectrum Family reactions usually exist on a nuanced spectrum, often characterised by “Validation Asymmetry”:

- Active Support: Genuine encouragement and celebration of your growth.

- Polite Silence: Neutral acknowledgement where the topic is avoided to prevent discomfort.

- Validation Asymmetry: This is particularly confusing. You expect recognition for a massive life change, but you receive silence. This happens because “celebrating” your change would require the family to “update their internal file” on you, which disrupts their sense of historical continuity.

- Subtle Sabotage: “Accidentally” topping up your glass or minimising your progress as “just a phase.”

Reflection/Analysis: Memory vs. Momentum There is a profound distinction between how families and external communities react to sobriety. Families hold your “archives”—they have a legacy version of you that they are often desperate to protect because it represents their own history and stability. External communities, such as new friends or sobriety groups, hold “momentum.” They meet the current version of you and are invested in who you are becoming, rather than who you used to be. Understanding this “cognitive lag” in families is vital. Your family may be lagging behind because they are still looking at the “archived” version of you, while you are already moving forward with new momentum.

6. The Internal Battle: Success Shame and Identity Friction

Not all the discomfort of sobriety comes from the outside. Often, the most intense friction is internal. This is the part of the journey few people prepare for: the feeling of guilt for finally doing well.

Success Shame Conditioning Many of us were raised with “Success Shame Conditioning.” We were taught—subtly or overtly—that visibility is a risk. Don’t show off. Don’t outshine your siblings. Don’t be too much. When sobriety removes the “chemical dampener” of alcohol, your energy, clarity, and posture change. Your nervous system, however, may interpret this expansion as a social danger. It remembers the childhood “corrections” and triggers a feeling of shame because you are “expanding” in a way that feels “risky” to your tribal wiring.

Identity Expansion Friction Alcohol often acts as both a sedative and a social lubricant, keeping your emotional range narrow and predictable. When you remove it, your identity begins to expand rapidly. You develop “The Smallness Habit”—a tendency to stay quiet to reduce friction. Sobriety removes the anaesthetic that made this habit comfortable. Suddenly, you notice your own potential with a clarity that can feel like arrogance.

Loyalty Conflicts You may experience a sense of “perceived disloyalty” toward those who still drink. The internal script often whispers: If I get healthier, am I leaving them behind? This isn’t logic; it is tribal wiring. We are evolutionarily programmed to stay with the pack, and “getting better” can feel like a betrayal of those who are choosing to stay where they are.

Reflection/Analysis: Removing the Anaesthetic For many years, alcohol was the anaesthetic that made “playing small” feel tolerable. It muted your awareness of your own potential and allowed you to fit into social boxes that were far too small for you. Once that anaesthetic is removed, the friction you feel is simply the sensation of your true identity expanding to fill the space alcohol used to occupy. This is not arrogance; it is recalibration. You are finally seeing yourself without the “muted” filter, and the resulting guilt is merely your nervous system trying to “protect” you from the perceived danger of being seen.

7. Debunking the “Fun Police” Label

One of the most common labels thrown at sober individuals is that of the “Fun Police.” This label is a classic example of “Perception Drift”—a result of contrast rather than any actual change in your character.

Perception vs. Action In social settings, alcohol acts as a “behavioural synchroniser.” When you opt out, that synchronisation breaks. You aren’t “confiscating drinks” or “banning parties”; you are simply existing without ethanol. However, because you are no longer “amplified” by alcohol, you appear “muted” by comparison. You are not being dull; you are simply “unamplified.”

Behavioural Optics Alcohol is an amplifier of expression. When everyone else is operating at an “amplified” level, the person at “baseline” (the sober person) appears unenthusiastic to the group. This is a matter of optics, not character. You haven’t lost your sense of humour; you’ve just lost the chemical urge to laugh at things that aren’t actually funny.

Reflection/Analysis: The Breakdown of Synchronisation The “Fun Police” label is a defensive reaction to the breakdown of “behavioural synchronisation.” When a group is drinking, they are participating in a shared chemical experience that validates their actions. By staying sober, you are opting out of this shared baseline. Your choice, though silent, highlights the “unnatural” nature of the group’s heightened state. They call you the “Fun Police” because your presence makes it harder for them to maintain the illusion that their “amplified” behaviour is the only path to connection. You have broken the synchronisation, and the label is their way of trying to neutralise the discomfort that the break creates.

8. Operational Tools: Logistics Over Willpower

Staying sober in a drinking world is not a test of your willpower; it is a matter of environment design and logistical preparation. Relying on “grit” in a room full of people pouring drinks is a recipe for exhaustion and a cortisol spike. Instead, you need “operational tools.”

Logistical Tactics

- Drive Yourself: This is the ultimate tool for autonomy. When you have your own transport, you are never “trapped” by the group’s timeline. This significantly lowers social anxiety by providing a guaranteed “exit window.”

- Have a Default Drink: Know exactly what you are ordering (e.g., “lime and soda, please”) so there is no moment of hesitation at the bar. Hesitation is where “normalisation pressure” finds its opening.

- Rehearse a One-Line Response: Have a simple, neutral explanation for not drinking that requires no further debate. “I’m not drinking tonight” is a complete sentence.

- The “Exit Window” Strategy: Decide before you arrive exactly when you plan to leave. When the “amplification” of the room reaches a point where conversation becomes repetitive or tedious, give yourself permission to exit.

- Track Milestones Privately: Given the “Validation Asymmetry” in families, seek validation from external communities who hold “momentum” rather than those holding “archives.”

As you move through this process, you will experience a transition from “hyper-awareness” to “procedural neutrality.” In the beginning, every social interaction feels like a high-stakes negotiation. You monitor every glass. However, over time, the question shifts from “Should I drink?” to the simple statement of identity: “I don’t drink.”

Reflection/Analysis: From Willpower to Identity The shift to “I don’t drink” represents the stabilisation of your new identity. Initially, sobriety is a conscious act—a task that requires constant vigilance. But as you repeatedly expose yourself to social situations, the “internal weighting system” of your brain changes. What once felt like an intense battle becomes “procedural”—just another part of how you navigate the world. Eventually, the alcohol in the room becomes “neutral” and then “irrelevant.” The room full of drinkers hasn’t changed, but your relationship to the “mathematics” of the room has. You no longer give the alcohol the power to dictate your comfort.

9. Conclusion: The Realisation of Alignment

The journey of sobriety eventually leads to a quiet, profound realisation: you actually like the person you are becoming. The social friction, the “weirdness” of the room, and the initial guilt of “expanding” are all part of a necessary process of “accurate alignment.”

You will find that your relationships change, but perhaps not in the way you feared. Sobriety acts as a diagnostic tool for the structural foundations of your connections. You will see clearly which relationships were built on shared values and which were merely built on “shared avoidance.”

“You are not losing people because you stopped drinking. You are revealing the structural foundations of your relationships.”

Ultimately, sobriety is not about seeking universal approval from the group. It is about “behavioural honesty.” It is about ensuring that your external actions match your internal values and that your life is no longer being lived according to “invisible contracts” you never agreed to.

As you look at your current relationships, ask yourself: Which of these are built on the firm ground of shared values, and which are held together by the “blur” of shared avoidance? The answer to that question is not a loss; it is the beginning of your true alignment.

Emotional Mastery: The Emotional Operating System

The Emotional Mastery book is a practical manual for understanding and regulating the human nervous system using the Emotional Operating System framework.

Instead of analysing emotions or retelling your past, the Emotional Mastery book teaches you how to read emotional states as system feedback, identify overload, and restore stability under pressure.

No labels. No therapy-speak. No endless healing loops.

Just a clear, operational approach to emotional regulation that actually holds when life applies load.

Instant digital download.