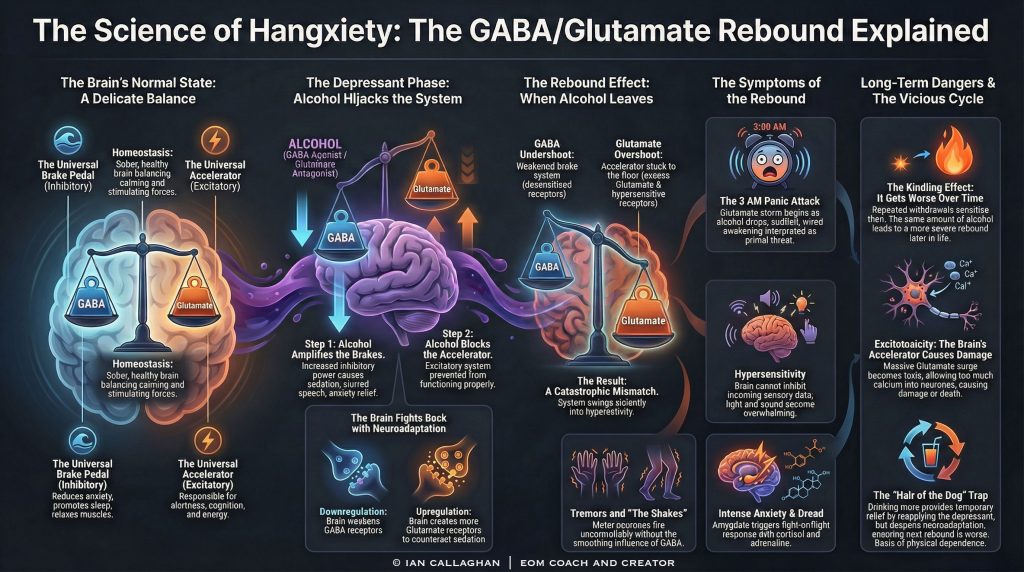

Why Hangxiety Strikes Hard? You wake up at 3 am with your heart hammering against your ribs, drenched in sweat, experiencing the GABA/Glutamate Rebound: The neuroscience behind why brain chemistry overcorrects after alcohol acts as a depressant, causing hyperactivity and panic. This terrifying physiological state is not merely a “bad hangover” or a sign of weak character; it is a predictable, violent swing of the neurological pendulum.

For years, society has treated the “jitters” or “the fear” following a night of heavy drinking as a purely psychological reaction to regret. However, modern neuroscience reveals that this phenomenon is a strictly chemical event. It is the result of your brain frantically attempting to restore balance after being artificially sedated. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for removing the shame associated with “hanxiety” and realising that the panic you feel is a biological response to the chemical loan you took out the night before.

This guide provides a comprehensive analysis of the neurochemistry at play, optimised for clarity and precision. We will dissect the interaction between the brain’s primary inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters to explain precisely why the brain overcorrects into a state of hyper-arousal.

The Neurochemistry of Balance: GABA and Glutamate Explained

To understand the Rebound, one must first understand the baseline state of the human brain. Your central nervous system operates on a delicate axis of electrical activity, maintained by two primary neurotransmitters that function as opposing forces.

Think of your brain as a high-performance car. To drive safely and effectively, you need a precise balance between the brake pedal and the accelerator. In the human brain, these roles are played by Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) and Glutamate.

GABA: The Universal Brake Pedal

GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. Its function is to reduce neuronal excitability throughout the nervous system. When GABA binds to its receptors, it opens ion channels that allow negatively charged chloride ions to enter the neuron. This makes the neuron less likely to fire an electrical signal.

In practical terms, GABA is responsible for:

- Sedation and Sleep: Slowing down racing thoughts to allow for rest.

- Muscle Relaxation: Preventing tremors and tension.

- Anxiety Reduction: acting as the body’s natural valium, creating feelings of calm and well-being.

Without sufficient GABA activity, the brain would operate in a constant state of seizure-like activity or extreme panic.

Glutamate: The Universal Accelerator

Opposing GABA is Glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter. It is the most abundant neurotransmitter in the vertebrate nervous system and is involved in cognitive functions like learning and memory. When Glutamate binds to its receptors (such as NMDA receptors), it facilitates the influx of positive ions, increasing the likelihood that a neuron will fire.

Glutamate is responsible for:

- Cognition and Memory formation.

- Wakefulness and Alertness.

- Reactive speed and Energy.

In a sober, healthy brain, GABA and Glutamate are in a state of homeostasis. They counterbalance each other perfectly. If you encounter a stressor, Glutamate may spike to help you react, followed by a release of GABA to calm you down once the threat has passed. This equilibrium defines a stable mood.

The Depressant Phase: How Alcohol Hijacks the System

When you consume alcohol (ethanol), you are introducing a powerful, dirty drug into this finely tuned system. Alcohol does not contain GABA or Glutamate, but it mimics the former and suppresses the latter. This is why alcohol is classified pharmacologically as a Central Nervous System (CNS) Depressant.

The GABA Mimicry

Alcohol acts as an agonist to the GABA system. It binds to specific sites on the GABA-A receptor complex (distinct from the sites where GABA itself binds), thereby altering the receptor’s shape. This structural change keeps the ion channel open longer and more frequently, allowing a massive influx of negatively charged chloride ions.

This amplifies the inhibitory effects of natural GABA. This pharmacological action is responsible for the subjective effects of drunkenness:

- Slurred speech (motor inhibition).

- Stumbling (cerebellar inhibition).

- Sedation (cortical inhibition).

- Anxiety relief (amygdala inhibition).

Essentially, alcohol puts a brick on the brake pedal.

The Glutamate Suppression

Simultaneously, alcohol acts as an antagonist to the Glutamate system. It specifically inhibits the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which are a subtype of Glutamate receptors. By blocking these receptors, alcohol prevents Glutamate from exciting the neurons.

This suppresses the brain’s electrical activity. It removes the foot from the accelerator. This dual action—hyper-activating the brakes (GABA) while cutting the fuel line to the accelerator (Glutamate)—results in the profound CNS depression associated with intoxication. The brain slows down significantly, which the drinker experiences as relaxation, confidence, or drowsiness.

However, the brain is a survival machine designed to maintain equilibrium at all costs. It does not passively accept this suppression; it interprets the presence of alcohol as a massive chemical blockage threatening its ability to function.

Neuroadaptation: The Brain’s Desperate Fight for Homeostasis

The human brain possesses a remarkable quality called neuroplasticity. It constantly adjusts its sensitivity to chemical signals to maintain a standard operating baseline. When you drink alcohol, especially in large quantities or over a sustained period (even just a heavy night out), the brain detects a critical imbalance: Inhibition is too high; Excitation is too low.

To counter this suppression and keep you alive (ensuring you continue breathing and your heart keeps beating despite the sedative), the brain initiates a process called upregulation and downregulation.

Downregulation of GABA Receptors

Because the GABA system is being hyper-stimulated by alcohol, the brain attempts to regain balance by reducing its sensitivity to GABA. It does this by:

- Internalising receptors: Literally pulling GABA receptors off the surface of the neurons so they cannot be activated.

- Desensitisation: Changing the structure of the remaining receptors so they require more GABA (or alcohol) to open.

The brain is essentially trying to cut the brake lines because the brake pedal is being pressed too hard.

Upregulation of Glutamate Receptors

Simultaneously, because Glutamate activity is being blocked by alcohol, the brain perceives a lack of excitatory signals. To compensate, it:

- Produces more Glutamate: It generates extra excitatory neurotransmitters to try to force a signal through the blockade.

- Creates more NMDA receptors: It builds new receptors on the neuron surface to catch any scrap of Glutamate available.

The brain is now slamming its foot on the accelerator and installing a turbocharger, trying to fight against the sedative effects of the alcohol.

While you are drinking, you do not feel this struggle. The alcohol (the external depressant) is powerful enough to keep the sedation in place, masking the massive buildup of excitatory potential underneath the surface. You feel drunk and relaxed, but underneath the hood, your engine is revving at 8,000 RPM just to keep idling.

The Rebound Effect: When the Alcohol Leaves the Building

This brings us to the crux of the issue: The GABA/Glutamate Rebound. This is the mechanism that defines the transition from intoxication to withdrawal (hangover).

Alcohol has a relatively short half-life. Depending on the rate of metabolism, the liver processes approximately 1 unit of alcohol per hour. As you stop drinking and go to sleep, your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) begins to drop.

The Unveiling of the Overcorrection

As the alcohol is metabolised and leaves your bloodstream, the artificial suppression is removed. The external force holding down the GABA brake pedal and blocking the Glutamate accelerator vanishes.

However, the neuroadaptation (the brain’s countermeasures) does not vanish instantly. It takes days, sometimes weeks, for receptor density to return to baseline.

The result is a catastrophic mismatch:

- GABA Undershoot: Your natural GABA production is now insufficient, and your receptors are desensitised/downregulated. You have virtually no “brakes.”

- Glutamate Overshoot: You have an excess of Glutamate and a surplus of hypersensitive NMDA receptors (Upregulation). Your “accelerator” is stuck to the floor.

Because the alcohol is no longer present to counteract the brain’s adjustments, the system swings violently in the opposite direction. This is not merely a return to baseline; it is a rebound effect that propels the brain into a state of hyperactivity.

The Physiology of the 3 am Panic

This chemical imbalance explains the specific timeline of the “hangxiety” phenomenon.

- Initial Sleep (0–4 hours post-drinking): You fall asleep easily because the alcohol is still present, acting as a sedative.

- The Rebound (4–6 hours post-drinking): As alcohol metabolises, the Glutamate storm begins. The brain shifts from slow-wave sleep to REM sleep, then to wakefulness.

- The Awakening: You wake up suddenly. There is no grogginess; you are “wired.”

The excess Glutamate floods the brain, causing neurons to fire rapidly and indiscriminately. This state of hyperexcitability manifests physically and mentally. The brain interprets this surge of electrical activity as an imminent threat, triggering the release of cortisol and adrenaline (epinephrine).

This is why the anxiety feels so physical. It is not a worry about what you said the night before (though that may come later); it is a primal, chemical panic attack caused by a nervous system that is firing on all cylinders with no ability to inhibit the signals.

The Spectrum of Rebound: From Jitters to Seizures

The severity of the GABA/Glutamate rebound exists on a spectrum, dependent on the quantity of alcohol consumed, the duration of drinking, and individual biological factors (genetics, history of use, and the “Kindling” effect).

Mild Rebound (The Common Hangover)

For the casual drinker whooverindulges, the rebound manifests as:

- Hypersensitivity to light and sound: The brain’s sensory processing centres cannot inhibit incoming data.

- Tremors (The Shakes): Motor neurons are firing without the smoothing influence of GABA.

- Irritability and Anxiety: The amygdala (fear centre) is hyperactive.

- Insomnia: An inability to fall back asleep despite exhaustion, due to excitatory neurotransmitter dominance.

Severe Rebound (Withdrawal)

In chronic drinkers or after a massive biRebounde rebound is more dangerous. The Glutamate storm can become toxic (Excitotoxicity). The neurons fire so rapidly that they can damage or kill themselves.

- Auditory or Visual Hallucinations: The sensory cortex creates data that isn’t there.

- Delirium Tremens (DTs): A severe form of alcohol withdrawal involving sudden and severe mental or nervous system changes.

- Seizures: The ultimate manifestation of unchecked electrical activity. Without GABA to stop the firing, a feedback loop of electrical excitation spreads across the brain.

It is vital to realise that the feeling of “doom” associated with a hangover is an evolutionary signal. Your brain is in a state of chemical emergency. The feeling that “something is wrong” is technically correct—your neurochemistry is critically unbalanced.

Why “Hair of the Dog” Works (And Why It Is Dangerous)

Understanding the GABA/Glutamate rebound explains the mechanism behind the “Hair of the Dog” (drinking more alcohol to cure a hangover).

When a person suffering from rebound anxiety consumes a drink, they reintroduce the GABA agonist and the Glutamate antagonist.

- Immediate Relief: The alcohol re-engages the brakes and suppresses the accelerator. The shaking stops, the anxiety fades, and the heart rate slows.

- The Trap: While this provides temporary relief, it resets the clock on withdrawal. The brain will respond to this new dose of alcohol by further downregulating GABA and upregulating Glutamate.

When this new dose wears off, the rebound will be even more severe. This cycle of drinking to aRebounde rebound is the neurochemical basis of physical dependence and addiction. The brain becomes unable to function without the external depressant because its own inhibitory system has been dismantled.

The Role of Kindling in Escalating Rebounds

Frequent cycles of intoxication and withdrawal lead to a phenomenon known as Kindling. Just as a small fire eventually builds enough heat to burn larger logs, repeated withdrawals make the brain increasingly sensitive to changes in Glutamate levels.

With each episode of the GABA/Glutamate rebound, the brain changes its structure to react more aggressively to future withdrawals. This means that over time, the “hangxiety” gets worse, even if the amount of alcohol consumed stays the same or decreases. A weekend binge that caused a mild headache at age 20 may cause crippling panic attacks at age 30 due to this cumulative neuroadaptation.

(End of Part 1)

The GABA/Glutamate Rebound: Why Panic Spikes After Drinking?

Understanding The GABA/Glutamate Rebound: The neuroscience behind why brain chemistry overcorrects after alcohol acts as a depressant, causing hyperactivity and panic, is the first step toward breaking the cycle of recurring anxiety.

The Neurobiology of Kindling: Why It Gets Worse

As touched on at the end of Part 1, Kindling is the neurological engine that drives the severity of the rebound effect over time. To fully grasp why a night out in your thirties feels vastly different to one in your twenties, we must look at the electrical changes occurring within the neuron.

Kindling refers to the sensitisation of brain neurones to repeated episodes of withdrawal. In neurology, this concept was initially identified in epilepsy research, where repeated low-level electrical stimulation eventually lowered the seizure threshold, making seizures more likely to occur spontaneously.

In the context of alcohol, the brain views the suppression of Glutamate (the gas pedal) as a threat to survival. Each time you drink heavily and then stop, the brain “learns” that its excitatory system was dangerously suppressed. To compensate, it creates a “memory” of this suppression.

The Structural Changes of Sensitisation

This memory is not psychological; it is physical. The brain actually alters its protein synthesis to prepare for the next assault.

- NMDA Receptor Proliferation: The brain builds more Glutamate receptors (specifically NMDA receptors) on the surface of neurons. This is like adding more ears to hear a whisper.

- GABA Receptor Insensitivity: Simultaneously, GABA receptors (the brakes) change their shape or internalise, becoming less responsive to your body’s natural calming neurochemicals.

When you drink again, the alcohol temporarily plugs these new, sensitive receptors. But once the alcohol metabolises, you are left with a brain that has “super-sensitive” excitatory hardware. This means that a minor drop in blood alcohol concentration triggers a massive, disproportionate spike in Glutamate activity. This hyper-excitability manifests as intense tremors, insomnia, and the sense of impending doom characteristic of The GABA/Glutamate Rebound: The neuroscience behind why brain chemistry overcorrects after alcohol acts as a depressant, causing hyperactivity and panic.

Excitotoxicity: When Activity Becomes Damage

The dangers of the Glutamate rebound extend beyond temporary discomfort or panic attacks. When Glutamate levels surge too high and remain elevated for too long, a process known as Excitotoxicity begins.

Glutamate functions by allowing calcium ions to enter the neuron. Calcium is essential for electrical signalling, but it must be tightly regulated. During a severe rebound, the floodgates open. Hypersensitive NMDA receptors allow a massive influx of Calcium into cells.

Why is excess Calcium dangerous?

- Enzyme Activation: High calcium levels activate enzymes that degrade cell membranes and proteins.

- Mitochondrial Stress: It forces the cell’s power plants (mitochondria) to work overtime, leading to oxidative stress.

- Cellular Apoptosis: In extreme cases, the neuron becomes so overwhelmed by electrical stimulation and chemical stress that it triggers apoptosis, a programmed form of cell death.

This is the neuroscientific explanation for “brain fog” and cognitive decline following heavy drinking episodes. It is not merely dehydration; it is a mild form of neurotoxicity caused by the brain’s own excitatory chemicals running wild.

Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS)

Many individuals believe that once the physical shaking stops and the hangover clears (usually within 24 to 48 hours), the Rebound is over. However, the neurochemistry of The GABA/Glutamate Rebound: The neuroscience behind why brain chemistry overcorrects after alcohol acts as a depressant, causing hyperactivity and panic operates on a longer timeline.

This extended phase is often called Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS). While the acute danger of seizure or severe panic may pass in a few days, the homeostasis of the brain takes weeks or even months to stabilise fully.

The Homeostatic Lag

- Weeks 1-2: Glutamate levels remain slightly elevated, and GABA levels remain suppressed. This results in “background anxiety,” irritability, and difficulty handling stress. Sleep remains fragmented because the brain cannot cycle into deep REM sleep efficiently without optimal GABA function.

- Weeks 3-4: The brain begins pruning the excess NMDA receptors (downregulation) and re-sensitising GABA receptors (upregulation). Mood stabilises, but cravings may spike as the brain seeks the “quick fix” of dopamine and artificial GABA stimulation.

Recognising PAWS is vital. Many people relapse during this period, not because they crave intoxication, but because they are desperate to stop the subtle, grinding anxiety of the prolonged chemical imbalance.

Nutrients for Neuroprotection: Mitigating the Rebound

While the only cure for Rebound is time and abstinence, allowing the brain to heal, specific nutritional strategies can support the restoration of homeostasis and protect against Excitotoxicity.

Note: This is information based on neuroscience, not medical advice. Always consult a healthcare professional regarding withdrawal management.

1. Magnesium: The Natural Calcium Blocker

Magnesium is perhaps the most critical mineral for someone suffering from the Glutamate rebound. Magnesium acts as a “gatekeeper” for the NMDA receptor. It sits inside the ion channel and blocks Calcium from entering the neuron unless a strong signal is received.

Alcohol causes severe magnesium depletion through the kidneys. When magnesium is low, there is no doorkeeper at the NMDA receptor. Calcium floods in unchecked, causing hyperexcitability and cell damage. Replenishing magnesium helps “plug” these receptors, dampening the excitatory noise and protecting the brain from Excitotoxicity.

2. L-Theanine: Glutamate Modulation

Found naturally in green tea, L-Theanine is an amino acid that mimics the structure of Glutamate. It can bind to Glutamate receptors without stimulating them as aggressively, effectively blocking the “real” Glutamate from causing chaos. Furthermore, L-Theanine has been shown to boost GABA production, helping to pump the brakes while simultaneously taking the foot off the accelerator.

3. Taurine: The GABA Agonist

Taurine is an amino acid that acts as a metabolic transmitter. Structurally, it is very similar to GABA. It can activate GABA receptors directly, providing a calming effect, and helps regulate the flow of Calcium in and out of cells, further reducing the risk of Excitotoxicity.

Lifestyle Factors: Avoiding the “Second Wave”

To successfully navigate the recovery from a Glutamate spike, one must avoid triggers that mimic the stress response.

Caffeine and Cortisol

Due to the Rebound, the nervous system is already in a “fight or flight” state. Caffeine is a stimulant that blocks adenosine (a chemical that makes you tired) and increases cortisol. Consuming caffeine during a Glutamate rebound is like pouring petrol on a fire. It amplifies the jitteriness and anxiety because the brain lacks the GABA cushioning to modulate the stimulant effect.

The Sugar Crash

Alcohol contains high amounts of sugar, and heavy drinking disrupts insulin sensitivity. A blood sugar crash (hypoglycaemia) triggers a massive release of adrenaline and Glutamate as the brain panics for fuel. Eating complex carbohydrates and protein helps maintain stable blood glucose levels, preventing secondary spikes in anxiety.

Summary: The Path to Homeostasis

The journey through The GABA/Glutamate Rebound: The neuroscience behind why brain chemistry overcorrects after alcohol acts as a depressant, causing hyperactivity and panic is a physiological ordeal, not a character flaw. It is a predictable, mechanical response of the central nervous system attempting to survive under the influence of a potent depressant.

The cycle of relief-and-rebound creates a trap where the cure (alcohol) becomes the cause of the next crisis. By understanding the mechanics of:

- GABA Suppression (The loss of brakes),

- Glutamate Surge (The stuck accelerator),

- Kindling (The worsening over time), and

- Excitotoxicity (The cellular damage),

…we can realise that “hangxiety” is not merely an emotional state, but a symptom of a brain in chemical distress.

Recovery is a process of neuroplasticity. The brain is incredibly resilient. Given time without the interference of alcohol, the brain will dismantle the excess Glutamate receptors, repair the GABA pathways, and return to a state of natural calm. The anxiety is not permanent; it is a temporary signal that the system is fighting to regain its balance.

Emotional Mastery: The Emotional Operating System

The Emotional Mastery book is a practical manual for understanding and regulating the human nervous system using the Emotional Operating System framework.

Instead of analysing emotions or retelling your past, the Emotional Mastery book teaches you how to read emotional states as system feedback, identify overload, and restore stability under pressure.

No labels. No therapy-speak. No endless healing loops.

Just a clear, operational approach to emotional regulation that actually holds when life applies load.

Instant digital download.